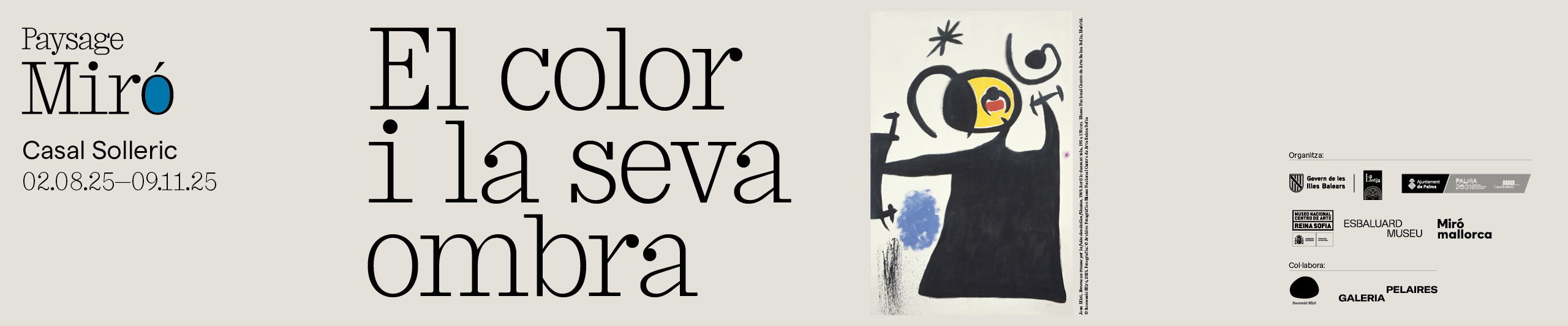

Paysage Miró. El color i la seva ombra - Casal Solleric

Paysage Miró. El color i la seva ombra

Joan Miró pointed out that time did not matter in his work and claimed to belong to the present. Indeed, the story of his career could be told through a series of concentric circles, and that is how this exhibition at the Casal Solleric is conceived, without a conventional chronological structure, in order to intertwine ideas that show his importance in the evolution of 20th century painting and sculpture, and to reveal the relationships the artist establishes between the two disciplines.

Joan Miró is a conceptual artist, and that is how we should understand his approach to painting and sculpture. His intent was always to transform the viewer’s perspective. That is why, from the outset, he tried to sidestep the traditional rigidity of both disciplines to pursue the conceptualisation of his symbols. Miró observes reality in order to distil it, and that is why he turns the female figure into a sign, like his schematic stars and other characters. But these references are not always visible, and these figures function as unanswered questions we can grab onto, lending meaning to the certainty that we have no way of apprehending the absolute or accessing the mystery, because any approach effectively entails a distancing. The field of the image, of the sculpture or the painting, falls away and the revelation of meaning becomes impossible, as though certain signs and images were swelling towards their own extinction. Because Miró created his own visual alphabet and what is missing from it helps us to assess what we see, to give it meaning, to generate tensions.

The exhibition “Colour and Its Shadow” is part of “Paysage Miró”, a joint project organised with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía and presented at four iconic contemporary art venues in Palma—La Llotja, Es Baluard Museu, Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca and Casal Solleric—with additional support from Successió Miró and Galeria Pelaires. Each of the four venues offers its own perspective, yet together they make up a single landscape. The current selection includes works created between 1960 and 1981 from the collections of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca and Es Baluard Museu.

Joan Miró began systematically producing his sculptures of enigmatic figures from the 1960s onwards. Of course, his three-dimensional work or his interest in volume were evident decades earlier, but it was at this point that Miró let loose his imagination in his cast bronze sculptures. Any object or pretext could cause Miró’s inspiration to overflow; he would walk around and pick up things that began forming a collection which, in turn, could be used in his assemblages, always paradoxical and taking inspiration from Dadaist or surrealist theories, but also with a strong connection to the land and to popular art. As though the artist were hoping to pile up and solidify the forms and the memories, so that those humble and fleeting gestures might become permanent through their new totemic nature. In them he plays with weight, with volume, with balance and with the unthinkable, like in his painting, where he also reveals an interest in trivial things, in primitive things that may look naive.

In general, Joan Miró’s sculptures have a lot in common with his more graphic paintings, where the support seems unprepared; the more austere paintings, which still have an intense plastic beauty, as is seen in many of the paintings on exhibit at Casal Solleric. Far from revealing the mystery, Miró expands it to keep the viewer at a crossroads, between what is internalised and what survives on the surface, what is left between parentheses, space as a pure absence that can permit all kinds of presences.

Joan Miró’s painting raises questions in us, perhaps because it is conceived in a reality that reminds us both of the primordial weight of the earliest cave paintings—with an ancestral logic that is even more evident in his sculptures—and absolutely contemporary questions that interrogate the practice of painting and sculpture, and which can be narrated through his work. On the one hand, the progressive destruction of pictorial space that shows us how the advent of abstraction was not planned, but rather the result of a drawn-out struggle for the autonomy of art with respect to its external reality and a desire on the part of artists to be able to paint the last possible paintings. On the other hand, how he manages to presage a kind of painting in which time can be experienced, a painting that ends up rejecting its margins. And finally, how his stance with regard to painting accepts its conceptual condition, independently of its figurative or abstract condition, or whether it is expressed through colour or form.

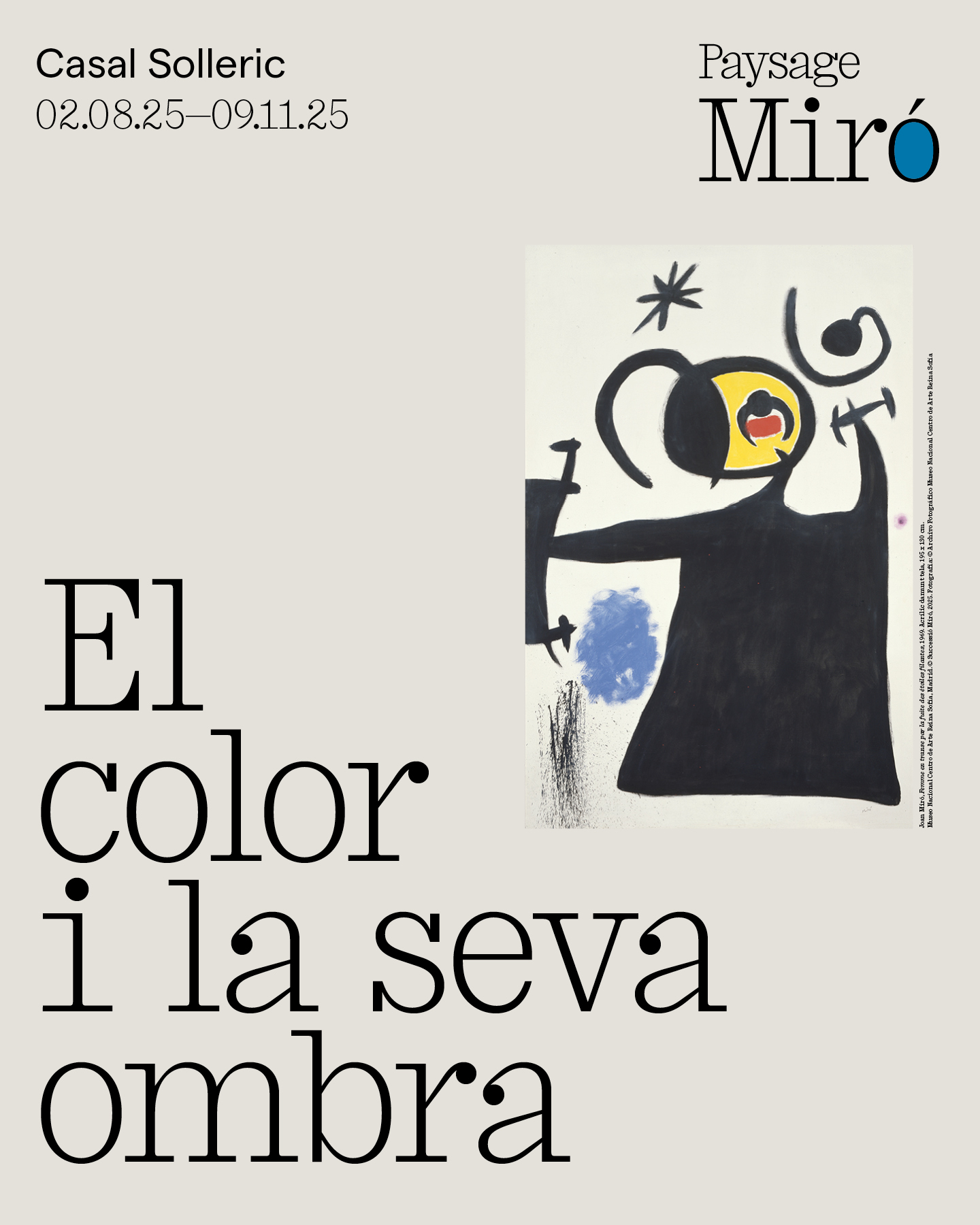

One of his obsessions in sculpture and painting was trying to aggrandise women, his femmes, which, in Miró’s work, symbolise the connection with the roots of the earth, with the provider of life. There are many, varied examples of this in the Casal Solleric exhibition. In some paintings, it is a black blotch and, in the sculptures, a volume to which other volumes are added. Because, truly, for Miró, la femme is a kind of universe, like his stars or birds, or his heads and his characters. Joan Miró looks in the rearview mirror and condenses centuries of art history. That is why he is a radically contemporary artist, and this assertion persists regardless of the decade in which each work may have been created. He is, if we consider how he wanted to “assassinate painting” through painting, or how he managed to translate his universe into sculpture and how he was able to combine his work with other crafts and artisanal traditions: weaving, mosaics, graphic arts, pottery.

While in Miró’s painting the narrative is put together from mystery, where information is offered at the same time it is withdrawn, and familiarity is combined with secrecy, in his sculpture, space is also extended so the viewer can speculate. This explains the tendency of his sculpture towards schematisation and simplifying forms, where his primitivism rises to the surface. After all, primitive illustrations are the beginnings of visual communication. If we can intuit a proto-writing in abstract geometric symbols, animal paintings could be read as pictograms or as the germ of Miró’s pictorial and sculptural art. The environment of the caves encouraged schematisation, and if we think about it in graphic terms, anything standing between a fire and a wall in the darkness becomes a silhouette. That is why Miró’s sculpture is shadow, and his painting is colour. This simplification is refined into an abstraction of the reality being represented, and this shadow of sorts that has literally seduced so many contemporary artists is present in Miró, who was not unaware of the achievements of prehistoric art and who repeatedly draws on tradition to begin his process of abstraction, which will never become an abstraction in itself. Because in Miró’s work, the ancestral sphere and popular culture always emerge, also in the way he engages with other media that are less qualified than painting and sculpture. Miró was an artist capable of elevating small things.

Paysage Miró. El color i la seva ombra

Planta Noble / Casal Solleric

August 2 - November 9, 2025

Opening: August 1, at 7:30 p.m.

Curators: Carmen Fernández Aparicio, Antònia Maria Perelló, David Barro i Fernando Gómez de la Cuesta

Co-produced with Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Museu Es Baluard and Fundación Miró Mallorca

From August 2, 2025 to November 9, 2025

Planta Noble / Casal Solleric

Date last modified: July 16, 2025